we wrote a story: script development

Due to an unexpected last-minute split with another group, it was something of a scramble to put together a proposal for the SIP. In light of this, I decided to take down an idea that had been sitting on my brain shelf for a while: adapting and developing an unfinished short story I'd written back in 2021.

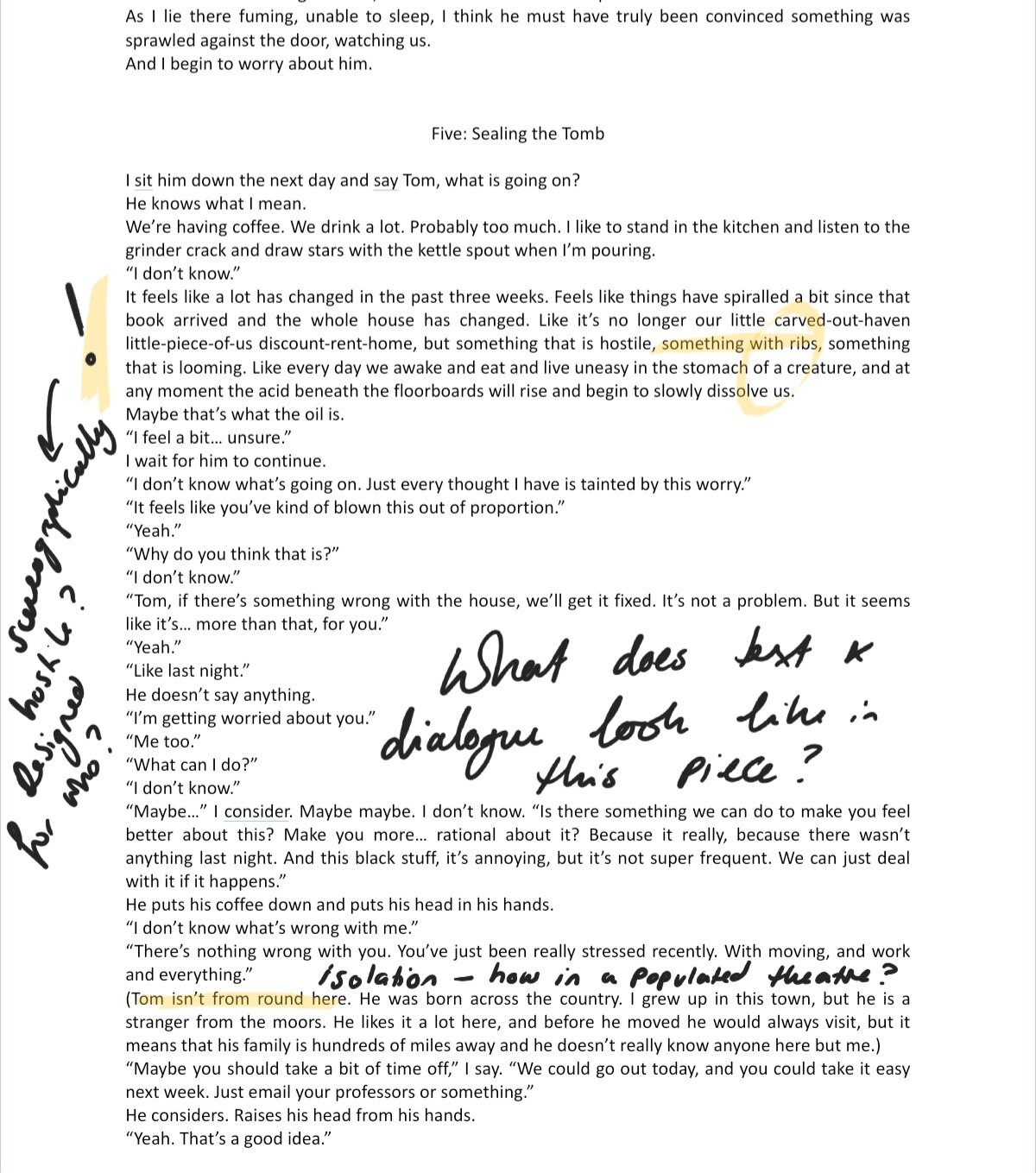

The operative word being ‘unfinished’; I had 4000 words that petered out because the real life experiences I wrote the story in response to hadn’t finished. The real story, if you like, didn't have an ending.

Nevertheless, I whacked the unfinished story up on our Google drive with the title ‘STIMULUS TEXT’. Haeyoung read it, I revisited it, and we combed through trying to find images, ideas or dynamics we thought were exciting and could translate onto the stage.

Once we’d gone through the stimulus text separately, we came together and discussed the ideas it had given us, things we wanted to use, and how the structure and expression might lend itself or be adapted for a piece of theatre.

In these discussions, we identified pretty quickly that we needed a base of normality and a progressive accumulation of unfamiliar or weird Happenings. We thought that the joy of theatre is that we could very easily extend or mirror these Happenings into the performance mode and generic form of the piece, and that would be very fun to explore.

We quickly found that we were at our most playful and experimental doing long form improvisation based around loose beats we predecided that we wanted to try.

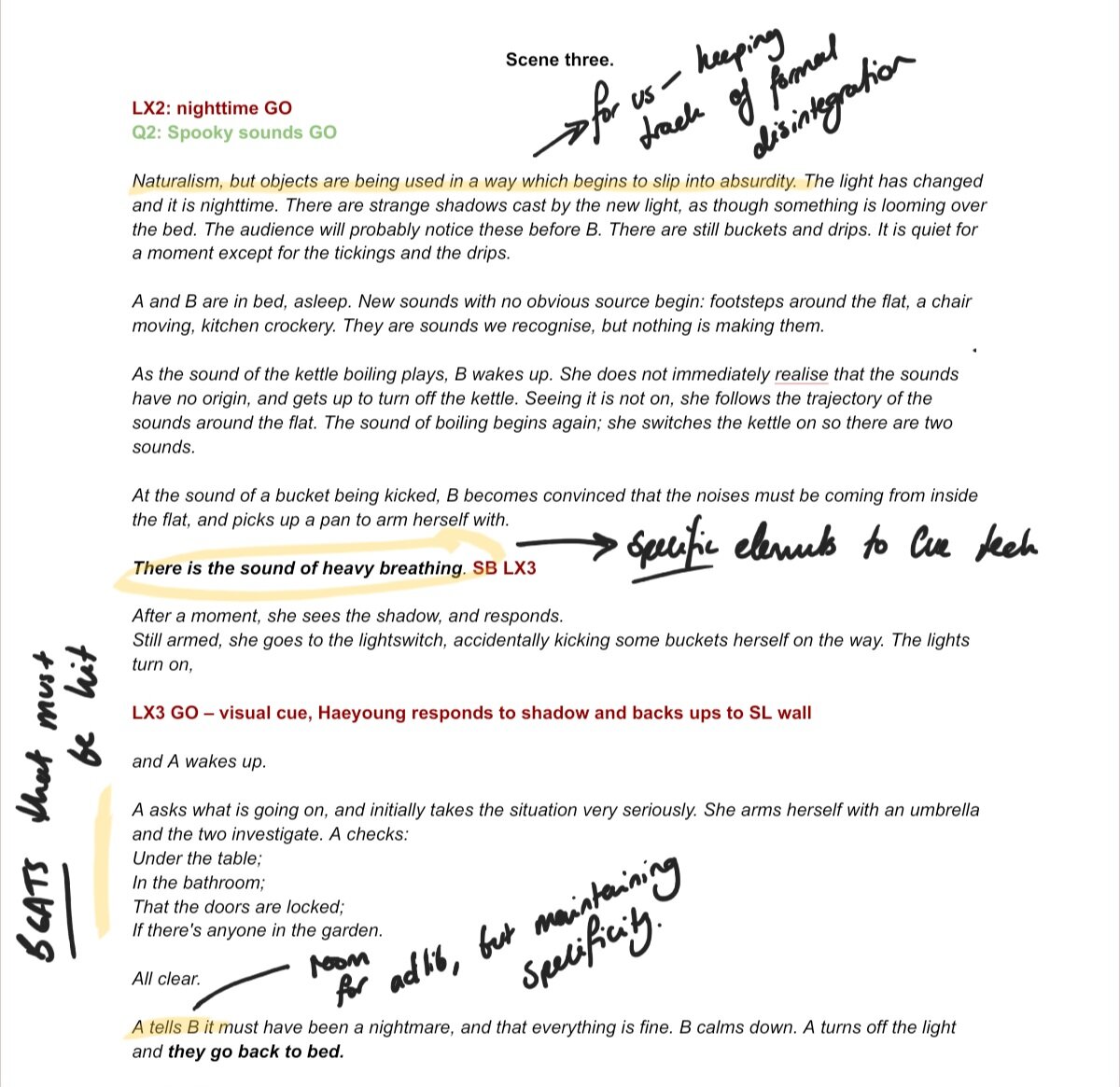

One early experiment for the shadow scene included the characters essentially Don Quioxte-ing themselves with household objects to create armour and weapons to defend against the creature with. The prominence of the pasta was also a result of these object exercises: we wanted to see how the relationship with the same object could change depending on whether we were human or puppet, and whether the role of the object could be fundamentally impacted by treating it with care or complacency.

From these exercises and improvisations, I would go and try to articulate what we had found into a clear score or script. Sometimes I would verbatim copy down phrases or exchanges we’d recorded. In terms of fitting all the moments we’d created together into one cohesive narrative, this came down to using our principles of escalation as a structural guide, writing moments down on separate pieces of paper and switching them about until we found the right shape or dynamic (and identified missing moments). That often looked like this:

As well as long form improv, we found we responded well to tasks and objects. We collected as many ordinary household objects as we could from Props and began to ‘build a home’ – we had these great empty rehearsal rooms and we filled them with pockets of clutter we could play with, feel comfortable in, improvise around and create stories with. The kettle and the tea were strong examples of this.

How do you score silence ?

How do you script the behaviour of a puppet?

How do you linguistically represent a repeated visual sequence?

But our piece was more than just objects and dialogue, which left us with some questions:

And how do we do that in a way that is legible and clear for our tech operator?

We tried a few versions, but ultimately settled on a language that was centred around beats (essential moments, movements or topics that had to happen) and suggestions (moments or ideas that had worked before, but weren’t essential), leaving the length and significance of particular elements up to the performers’ discretion and impulse of the moment. We always made sure to tie any tech cues to specific highlighted beats, and try to describe the action of a scene as clearly as possible without prescribing a tight choreography.

an encounter with our own bespoke vocabulary

I think the fluid and evolving language of scoring and the continually developing expression of the script spoke to and reflected our process. Our work was always cumulative, and always about refining our expression or clarifying the dramaturgical gestures that we used. It helped Haeyoung and I develop a rehearsal room language – something else which made the work feel very entwined with our personal journey through it. The process of parsing this for a tech operator was then surprisingly easy, as through scripting we had got such a firm grasp on the vocabulary of the piece that we did not struggle to expand our language to include them.